Onward Journey

An excerpt from the novella/anti-memoir, Anima + Angel … Includes notes on High Romanticism and the relationship of the concept of exile to the enlightened nihilism of the European Romantics …

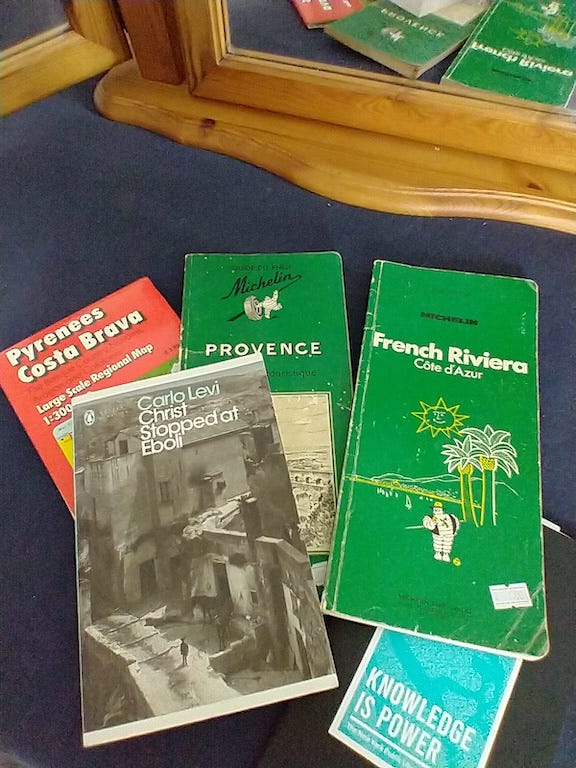

Image – Hypothetical Itinerary. Photo: Gavin Keeney.

[…]

JUNE 2025

On June 7, I returned to London from NW Wales … On June 8, Mercury and Jupiter met up at 29 degrees Gemini and prepared to travel across Cancer, Mercury leading the way. Options for “next steps” prior to Lucerne included Livorno, Italy. The main issue was the “distance” between June 7 and June 18, with June 18 being the intended arrival date in Livorno. While in Wales, in Aberdaron, I had visited a small church on the edge of Cardiff Bay on the Llŷn Peninsula. The church was empty – i.e., no one was there – but there was a small gift shop with various things for sale, including used books and maps. I found three maps in this collection, for 1.00 GBP each, that seemed to represent some sort of itinerary. They were: Catalonia (Costa Brava); Provence; and Côte d’Azur. This might be one route to Livorno – i.e., from Spain across the South of France to Italy (by train) … I purchased all three maps and made a 5.00 GBP donation.

[…]

THE ROMANTIC MIND

While in Wales, I found a book on the Romantic mind amidst the rather vast collections at Plas Gelliwig that spoke to my (un)certain condition regarding “exile.” It summarized many of the prevailing concerns of the English, French, German, and Italian romantics, confirming what I had read in Camus’ The Rebel during the ZRC SAZU thesis years. All in all, the Romantic disposition was one of “exile,” and the longing for the Absolute or Eternal was the selfsame as the Else-where sought across the years of 2011-2021 (2014-2024) – i.e., the years of the two PhDs.

“The idea of immortality, too, appears in a pantheistic garb: ‘In the midst of the finite to become one with the infinite and to be eternal in one moment, this is the immortality of religion.” F.E.D. Schliermacher, in H.G. Schenk, “Emotional Christianity,” pp. 110-115, in H.G. Schenk, The Mind of the European Romantics: An Essay in Cultural History (London: Constable, 1966), p. 115.

“Examples of Romantic longing for extinction are only too numerous [...] Lord Byron’s letters of 1823-4, as well as his poem ‘On this day I complete my thirty-sixth year’, justify the surmise that, weary of life, he went to Greece to die. Finally, Shelley, in the face of grave warnings, embarked on his fateful voyage from which he was not to return. Shortly before, Jane Williams had said of him: ‘He is seeking what we all avoid, death.’ There exists, of course, also strong internal evidence for Shelley’s Weltschmerz in the last years of his life, not only in the ‘Stanzas written in Dejection’ (1818) and the story ‘Una Favola’ (1820), where the poet is in love with Life and Death, two mistresses, of whom Death is a true lover, but still more conclusively in the symbolic dream poem ‘The Triumph of Life’ which has remained a torso. In Rousseau’s speech, the central part of the poem, Shelley’s political disenchantment reaches its climax. Shelley had now come up against the problems of evil for which there was no room in the panaceas of youth. But the evil has no counterweight; he did not perceive the existence of divine mercy. Nor did he share the belief in personal immortality. His restless search was nearing its end, and in the concluding drama Hellas he epitomized the Romantic hope of repose: ‘The World is weary of the Past:/ Oh might it die or rest at last!’” Schenk, “The Lure of Nothingness,” pp. 58-65, in ibid. pp. 64-65. Schenk, in the ellipses inserted above, goes on to list Romantics who died young and/or contemplated suicide in real life or through literary “reflections” (works) and reckless behavior (e.g., duels). They include: Friedrich Schlegel, Goethe, Chateaubriand, Foscolo, Vigny, Senancour, Lenau, Lamartine, Musset, Mickiewicz, Von Günderode, José de Larra, Nerval, Beddoes, Pushkin, and Lermontov.

[…]

I sampled the book in search of clues as to where my present journey was leading, suspecting that the implied dance with Fate endured by the Romantics could only be countered (or aced) with the attendant dance with Grace. Fate + Grace ... To not fear death or failure seemed to be the main (Romantic) point, and this more or less dovetailed with the longstanding Franciscan component of the two PhD agendas across ten years. Schenk’s book (essay) included a preface by Isaiah Berlin, which was rather stunning in its overall “placement” of the Romantics in “intellectual history.” Many of Berlin’s statements were also absurd (totalizing), insofar as there was, of course, no singular Romantic “mind.” Yet, his ability to make sweeping judgments on behalf of Big History seemed to confirm that historians were generally blinded by historicist sublations (pace Hegel et al.) – e.g., that all Romantics viewed life as singularly tragic and most met with a tragic end of one kind or another, self-willed or otherwise. Berlin (referencing Fichte): “The activity, the struggle is all, the victory nothing.” In Fichte’s words: “Frey seyn ist nichts; frey werden ist der Himmel.” (“To be free is nothing; to become free is very Heaven.”) Isaiah Berlin, “Preface,” pp. xiii-xviii, in ibid., p. xvii.

Schenk ended his book (essay) with a chapter on Nietzsche, whom he claimed sought an exit through malady (madness). Perhaps, not unlike Hölderlin, Nietzsche had had quite enough of his times by the time he reached Turin and used the senseless beating of a horse witnessed there as his ultimate excuse to “check out.”

“Nietzsche’s mental collapse has been examined from many different angles […]” “It is perhaps legitimate to surmise that the precise factor making for the final collapse was what Sigmund Freud would have called Flucht in die Klankheit (escape into malady). Lou von Salomé, who knew Nietzsche as well as anybody certainly had the impression that he had been craving for such solution. As soon as it came, the unbearable and ever-mounting tension at which he had been living for so long immediately disappeared, as is shown in his note to Peter Gast which reads: ‘Sing me a new song: the world is transfigured and all heavens are glad.’” Schenk, “Epilogue,” pp. 233-47, in ibid., p. 245; footnote 30 (p. 283) supplies the critical detail for this note to Gast: “The Date of the Postmark, Turin, 4 a.m., 4 January 1889.” Here Nietzsche is clearly echoing Fichte.

F.N. to Lou von Salomé: “Once everything has been run through – whither is one to run then? If all potential permutations were exhausted – what would follow? Why? Would one not have to come back to faith? Perhaps Catholic faith? In any case, going round in a circle would be more probably than standing still.” Schenk, ibid., pp. 243-44; see Lou Andreas Salomé, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, 8 vols. (Vienna: C. Konegen, 1894), pp. 50, 155. See also: Karl Schlechta, “Nachwort,” in Friedrich Nietzsche, Werke in drei Bänden, 3 vols. (Munich: C. Hanser, 1954-1956), Vol. III, pp. 1451-52 (Schenk, p. 283/fn 25, in ibid.). According to Schenk, Schlechta states: Despite all of its “blasphemous frenzy,” Zarathustra “also contains passages in which a much softer and mysterious countervoice may be discerned.” Schenk, ibid., p. 243. The statement made by Nietzsche to Lou Andreas Salomé clearly references the concept of the Eternal Return of the Same as developed in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-1885). This was, after all, Nietszche’s summary of the abject (versus enlightened) nihilism we would all have to pass through to reach “Else-where.”

[…]

Livorno was not far from where Shelley reportedly washed up on shore following his own game of playing chicken with Fate. Perhaps that was one reason to travel there – to “see” the place of taking place of Shelley’s ultimate embrace of exile.

As of June 8, the onward journey thus looked like this:

LONDON – June 7-TBD

ARENYS DE MAR – TBD-June 16

LIVORNO – June 18-TBD

LUCERNE – June 29-July 4

[…]

PDF version via secure link …

https://drive.proton.me/urls/G623HQF5ZW#9UhGv5onPDPV

[…]

OUTTAKES

P2P Update 1.2

Précis for a study of why Dante is a Franciscan artist-scholar … Includes a discussion of the legendary “dance” between Giotto and Dante …

Prelude to Exile

“There is no leader, there is no teacher, there is nobody to tell you what to do. You are alone in this mad brutal world.”