“Michelangelo” @ The British Museum

A review — “Michelangelo: The Last Decades,” The British Museum, London, England, UK. May 2-July 28, 2024. Curated by Sarah Vowles et al.

A review — “Michelangelo: The Last Decades,” The British Museum, London, England, UK. May 2-July 28, 2024. Curated by Sarah Vowles et al.

The exhibition “Michelangelo: The Last Decades,” at The British Museum, is “out of this world” for reasons that transcend the intentions of The British Museum. The entire thing is “epistolary.” It is “as if” Michelangelo is still penning letters, from the grave, to counter the impressions left by hagiographers that he was a tormented, solo genius. The letters attest “otherwise,” and these letters are both actual and phantasmatic: in the former case, they are actually present as documents borrowed from various collections; while in the latter case, they are clearly not-present but in the air (or ether), as if perhaps some curator-conjurer has tapped into a conversation between spirits, the spirit of Michelangelo being but one of numerous interlocutors.

The drawings supplementing the tale the exhibition wishes to tell of his last decades, in Rome, are part of this conversation. The totemic figures of his religious (biblical) depictions of, for example, The Passion, The Deposition, or The Annunciation all are not present insofar as they have become spectral presences.

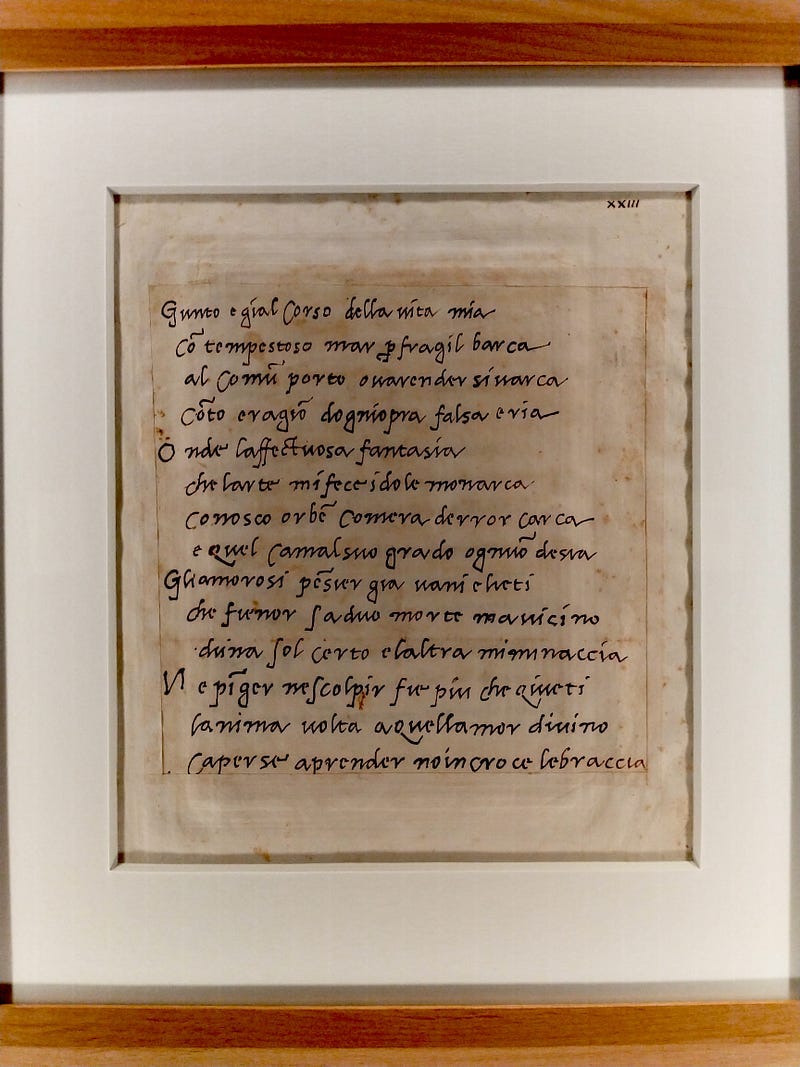

Michelangelo’s handwriting is, however, ever-present. Translations via wall text tell us just what he might have been up to in his various exchanges with friends, family, and collaborators. If The British Museum’s main point with the exhibition is to demolish the legend of the lonely and tortured genius, it only half succeeded. No matter how many letters staged to illustrate his extended circle, Michelangelo is still a lonely and tormented genius. The only difference here (as if it needed to be stated) is that he was not alone in his loneliness; and he was not the only tormented soul in a time when the Church was rapidly closing in on any remaining “republican” sentiments present as a result of the Reformation. The works on display “cross” the years of the Counter-Reformation, in a very similar and peculiar manner similar to the late works of El Greco. The exquisite monstrosities of The Last Judgement (1535–1541) are more than met with equal monstrosities in El Greco’s late works — for example, The Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608–1614). Did El Greco really get thrown out of Rome for insulting Michelangelo? Michelangelo had already passed into the stars when El Greco arrived in Rome. More than likely he insulted the hagiographers of Michelangelo.

This all brings up the greater mysteries of auto-hagiography as an art form — a very subtle art form or a very vulgar art form. It may be said that the exhibition trips over this mystery (stumbles upon it and then re-contextualizes it for semi-historical affect). What transpires as one walks slowly through the circular spaces of the gallery is that almost all of these relics (letters, drawings, testaments) converge at some ultra-sacred place where Michelangelo’s spirit resides. Let’s call it the Empyrean, after Dante (and there is a moment in the exhibition where Dante appears very briefly and then disappears entirely). Let’s say that art history cannot touch this place. Let’s say that one of the few arts that can touch this place is the written word. And let’s add for emphasis that in such cases the word becomes image, and that the image becomes a semaphore for the rites of passage endured.

Michelangelo must have worked incessantly each and every day to pull off what is on display and/or inferred in the exhibition. The architectural commissions alone are enough to drive anyone insane. The British Museum is, therefore, ardently wishing for us to know that he had collaborators. They (the curators) do not quite say that he had a workshop, but if one buys into this line of thought his collaborators become a de facto workshop, just as most all successful artists of the Renaissance hardly worked alone. “Production” was writ large in this day and age, and commissions came with/atop commissions. The aristocracy and the Church both wanted the best talent available to “tell” their story. Yet the strangest irony of all, which only dawns upon one when completing the circuit of the exhibition, is that Michelangelo was, after all, telling his own story, and, despite all claims otherwise by art historians and/or hagiographers, he had — at least in his “last decades” — the upper hand in all commissions otherwise intended to serve Power.