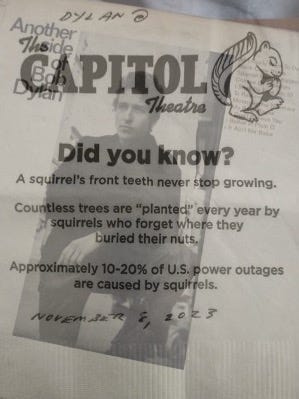

Dylan at the Capitol Theatre, Port Chester, New York, November 8, 2023

EPIGRAPH

“If the genius is an artist, then he accomplishes his work of art, but neither he nor his work of art has a telos outside him. Or he is an author, who abolishes every teleological relation to his environment and humorously defines himself as a poet. Lyrical art has certainly no telos outside it: and whether a man writes a short lyric or folios, it makes no difference to the quality of the nature of his work. The lyrical author is only concerned with his production, enjoys the pleasure of producing, often perhaps only after pain and effort; but he has nothing to do with others, he does not write in order that: in order to enlighten men or in order to help them along the right road, in order to bring about something; in short, he does not write in order that. The same is true of every genius. No genius has an in order that; the Apostle has absolutely and paradoxically, an in order that.”

— Søren Kierkegaard, Of the Difference between a Genius and an Apostle, in The Present Age: On the Death of Rebellion, trans. Alexander Dru, The Resistance Library (New York: Harper Perennial, 2019), pp. 86–87. Written in 1847. This translation first published by Oxford University Press under the title The Present Age and Two Ethico-Religious Treatises in 1940.

THE IMPOSTER

Dylan remains the consummate comedian and imposter. This is the only answer possible, for anyone experiencing his Wednesday night performance on November 8, 2023 at the Capitol Theatre, Port Chester, New York. His presence is his proverbial absence. And his presence, Wednesday, November 8 at the Capitol Theatre, could only be characterized as diminutive. He has been shrinking slowly, quite literally, as he ages. Yet the only trace of that older, sneering and contemptuous version of Dylan was hidden in the lyrics. His so-called stage presence was also notably modest, even exuding a bit of contrition for being a monster over the years. He sat at his piano the entire (roughly) one-hour-and-forty-five-minute set, rising only occasionally, but never leaving the piano — with the piano now a prop, much like his cowboy hat (or whatever style it was that he occasionally donned, semi-neurotically, between songs). His style of playing piano seemed intentionally simplistic, almost honky-tonk or dance-hall, though he was capable of much more. It grew in its implicit charm across his extended set.

The two songs that stood out were “I Contain Multitudes” and “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” both from Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020), at least in terms of the magnitude of what he was attempting to convey. He was once again deconstructing identity and subjectivity, all the while knowing his exploits across the decades of the second half of the twentieth century and the first quarter of the twenty-first were heroic. The comedic element was redolent with a sense of absurdity in chasing any absolute. There was no sign of the troubadour of the early 1960s. There was little if anything that could be taken extra-personally — i.e., as being politically, culturally, or religiously charged. Even “Gotta Serve Somebody” came off as a kind of return to Dylan-esque burlesque, not religion per se — with its supposed origin being his 1970s’ “conversion” to Christianity. It was all transpersonal, in the manner of his heroes — the poets of the past. Yet … There was always and ever-present a mysterious remainder — in attitude projected, modest (im)modest demeanor (a.k.a. persona), and lyrical ambiguity — a nod to apostles and prophets versus poets. Perhaps it was a nod to poets as prophets (or prophets as poets). Here, November 8, 2023, “He” (“I and not-I”) was once again lurking in his own shadows, eventually stepping forward, when it was “all said and done,” to courteously bow to the audience and bid us all “A-dieu” … Swan song after swan song. That would be one way of summarizing the effect of his performance. “I’m on my way out …” “God bless You.” (Did he bow? Did he say, “God bless You”? Perhaps “I” only saw and heard such. It was “one of those nights” …)

The presence of “When I Paint My Masterpiece” (1971) was riveting. He was still at it — still painting (with words). He knew this. His stage presence was as “Imposter” (capital “I” required, as homage to his serial destruction of personal identity over many years, that idealist battle between “I and I” always present, and his own embrace of the magical-iterative nature of poetry and songwriting). As an Imposter, Dylan was also metaphorically diminutive behind his piano. His usual attire of glittering black clothes was just a relic from the (cowboy) past. The lock of hair hanging over one eye suggested a late burst of High Romantic rebellion in an otherwise “aging” troubadour who long ago threw the baby out with the bath water. His rebellion was against himself, even as he posited yet another version of himself through which to stage his endless “good-bye.”

In a way, the entire performance (and perhaps the entire tour) was a case of “identity check” — or, a clever dance with his audience, not all aging and not all necessarily along with him for the long ride. He was checking his own identity as he passed through “security” en route to yet another departure’s gate, perhaps the ultimate one. The Capitol Theatre performance might have been classic de rigueur — along the arc of the long Rough and Rowdy Ways tour — with subtle shifts only recognizable by the Dylan cognoscenti or illuminati. They would, no doubt, be reporting on the subtleties of it all in blog posts and documenting the playlist (which appeared to be plastic-covered sheet music on the piano, obvious at times as he flipped pages). As for the band, their splendid significance was yoked to their splendid insignificance. Round and round they went in a kind of circularity of beat and rhythm that suggested the song book on display was orchestrated to feature Dylan’s latest (and perhaps last) style of delivery — a terse, expressive staccato — each phrase reduced to a totemic something indescribable, short line after short line (as if he was short of breath), and in the manner of poetry that is attempting to present itself as utterly autonomous of the author, whether through restriction or encryption.

The Imposter on stage at the Capitol Theatre at Port Chester, New York, on November 8, 2023, was the rebel poet; the immortal and faux-amoral one Dylan always mimicked and which he had now — accidentally and on purpose — become.

CODA

No photos were permitted in the Capitol Theatre on the night of November 8, which makes sense. All cellphones were duly locked in a gray pouch after digital tickets were scanned, upon entry. Everyone was searched (patted down), and some of us were scanned, as at TSA checkpoints at any US airport today. Our own personal departure’s lounge for the night was our complicity in the event. Times certainly have a-changed. Gone are the glory days of the Capitol Theatre, even though images of those days are present on the walls of the first-floor bar/lounge, where today you can buy a glass of wine for 17.00 USD. You can also buy a can of Modelo beer, for 9.00 USD at the bar, or for 13.00 USD from a wandering vendor working the floor. It all makes sense in the sense of “cents” — i.e., percentage points and usurious profit margins given to the End Times that Dylan may have been subtly referring to — a slow and ever-encroaching levy on subjects privy to being subject to such events and rites for being permitted to have no actual or real rights under Late Capital. Dylan certainly was not out to maximize his profits. Or so it seemed. The Capitol Theatre is a small-ish venue. It cannot be about money anymore, at least for Dylan. He has all that he needs after selling his songwriting catalogue, oddly also in 2020, and estimated at 300 million USD by The New York Times.

What was it all about then? The Rough and Rowdy Ways tour is one of those incessant affairs, “rolling toward oblivion” since 2020. It is not unlike Leonard Cohen’s endless tour before his (un)timely demise, notably at the time of the “arrival” of Trump. “You want it darker?” Cohen asked, as he prepared to check out (depart this world) on November 17, 2016, almost exactly seven years before this particular “night at the opera” with Dylan. Dylan, the poet-troubadour-prophet, apparently still had something to say to us. I wonder if we “heard” it — or if we are even capable of hearing it any longer.